When I research photo collections, nothing makes me happier than finding crop marks. And crop marks on contact sheets of medium format film (or larger) really are fantastic because so much of the detail of the image is clear, and the intention of the markings is usually more apparent. Crop marks make visible what is normally invisible to us … the reshaping and reimagining of the image long after the point of exposing a film emulsion to light. They can be produced by the photographer, an editor, a client – anyone with an interest in how, and in what form, the photograph will circulate. They are usually done to suit the next stage of the post-photographic process, which means that cropping is not simply an aesthetic statement (although it can be).

Crop marks are an act of foreshadowing, a projection of what might be. Unlike most images captured on a contact sheet, those with crop marks have been chosen for printing, and thus will find new life in some print form. The act of cropping, then, implies the next stage, this new context. And even the new print is not intended (usually) to sit in isolation, but is imagined as a part of a new layout, a new format, a new ‘home’ for the image with new relationships produced and forged in the discursive spaces of conversations with other texts and images around it. Whether on an editorial page, an advertisement, or an exhibition gallery, the marking of a contact sheet is the first stage of imagining that picture in this new space.

The materiality of the photograph is an essential element to understanding what “cropping” means. Positive colour transparencies (such as slides) have a special relationship to cropping, because there’s very little that one can do after the photograph is taken. The exposure, the horizons, the composition – none of this can be changed after the fact through later darkroom techniques or (today) digital postproduction. Cropping was the one thing that could be done, as long as the remaining image didn’t get too small. So during my parents’ camera club slide shows I recall lots of discussion and talk about cropping, both in critiquing images to promote better composition, and in suggesting ways to enhance an existing slide. The process was accomplished by taking the film out of the cardboard edge holder, laying it on a light table, carefully masking the side that needed to be hidden from view with special tape, and then re-mounting it in a holder. Of course the crop taping needed to be absolutely straight and perfectly parallel, or else you were in trouble.

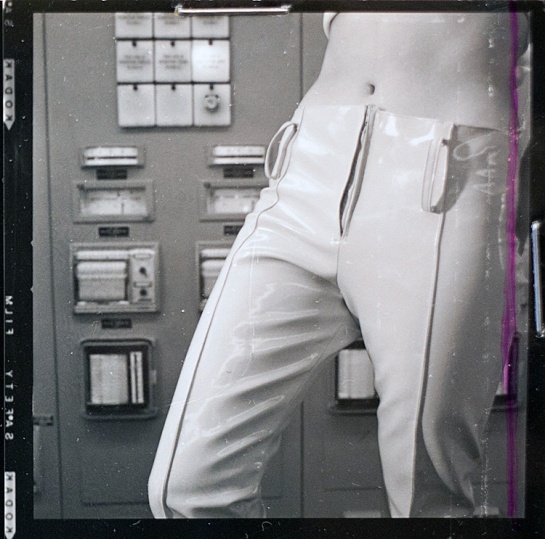

Detail of one frame from a contact sheet with crop marking, 1967. Photographer unknown. Imperial Oil Collection, Glenbow Archives.

With negatives, where the intended output is usually a positive print, cropping is often expected and, indeed, planned. Photographers frequently allow a bit of spillover in the edges because it’s easier to crop it out than to put something back in from beyond the frame. In the picture above, slicing off the right-hand side gives the impression of slimness and keeps the eye focused on the shiny PVC pants on display.

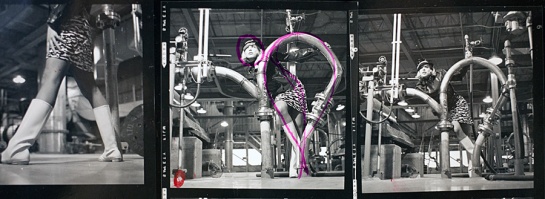

The process of cropping can be rendered invisible when the decisions are made on the fly, literally in the darkroom with only eyes of the print developer aware of what she or he is putting in or leaving out. However, in the larger corporate world of visual production, where different people are involved in the production process (editors, designers, photographers, darkroom technicians, admen, creative directors, clients, etc.), crop marks on a contact sheet reflect a chain of command that inscribes a set of decisions. Crop marks are a kind of “memoranda” issued by executives or middle managers to the technicians who do the actual work in producing the print. They are expressions of power that reflect not only a reshaping of the image, but also point to organizational processes, and social/economic hierarchies. It’s unclear if the markings below are for actual cropping, or point to directions for dodging/burning or some other reworking of the negative. The image does not stand on its own, but seemingly calls for the intervention of the purple marker.

Detail of three frames from a contact sheet, 1967. Photographer unknown. Model: Barbara Fulton. Imperial Oil Collection, Glenbow Archives.

It’s easy to jump from negative or print, or from print to image, without thinking about the middle stages of production. These points of transition carry the inscriptions of power that mark off not simply what frame to use, but also what parts of the frame to focus on. They determine what can and what can’t be seen, extracting a very small slice from a much larger set of cultural negotiations that surrounded the photographic session to begin with.

For copyright reasons, most of the contact sheets I work with can’t be reproduced here, without considerable red tape, but the Glenbow Archives generously granted me verbal permission to post images I came across while researching advertising photographs in the Imperial Oil photographic collection. I haven’t yet found where these particular images were used, but they were taken in September, 1967, at an Imperial Oil PVC plant in Sarnia, Ontario. The model is identified as Barbara Fulton, described as an “Esso Reporter, writer,” and she likely worked for the company’s internal magazine. So we have an employee recruited to model PVC clothing at a PVC plant for an oil company, and we simultaneously have a writer’s body being re-inscribed by the editorial marks that will direct how her image is refined and processed. And before we can hold the final print in hand, the photograph will need to go through yet more layers of mechanical and chemical alterations. It is here in the crop marks where we really see the point of collision between cultural, the aesthetic, the corporate, and the technical.

Detail of a contact sheet, 1967. Photographer unknown. Model, Barbara Fulton. Imperial Oil Collection, Glenbow Archives.

Of course, especially in the context advertising photographs in the 1960s, the editorial crop marks re-assert a masculine gaze. Fulton’s words may or may not have accompanied a magazine story about the Sarnia plant or the PVC clothes she was wearing, but she likely had no role in choosing which images to illustrate the story, or how those images were re-framed, re-cropped, and re-imagined. Exposing the hidden processes of cultural production calls attention to such acts of erasure, and reminds us that the photograph is not, and has never been, a stable or fixed entity.